The movie was--well, moving. Sitting on a dark plane surrounded by hundreds of sleeping strangers in the early hours of the morning, I found myself weeping for the dead and the anguish of the survivors and shuddering at the horrors of extensive injuries. I can point out what I think are some flaws in tone or story-telling, but I thought that the acting was great and the portrayal of the catastrophic tsunami was pretty amazing. I came home and looked it up on wikipedia and imdb and was unsurprised to see that the reviews were mostly good, but that it received some criticism for "white-washing", or telling a story affecting people of minority ethnic or racial groups with white actors to appeal to a mainstream white audience. It caused me to reflect on my impression of the movie and ask myself if I agreed; while I determined that I did not, I found this argument to be compelling and worth addressing.

I asked myself, what if the movie went about telling a story of a Thai, or Sri Lankan, or Indonesian family who suffered loss and injury in the tsunami? For starters, the essential nature of the film would be different. The exposition would require more detail to give the western audience the necessary background to understand something about the lives of the characters, leaving less time to explore the nature of the catastrophe and its aftermath. The filmmakers would also need to find a way to hook the audience into relating to people whose lives are so different. The movie would then shift in tone from being about the tsunami's destruction and the fragility of human life, and become an exploration of how we are somehow unable to feel the same compassion for people we identify as different (dare we admit that in the unexamined parts of our consciousness, we even consider inferior?) from us.

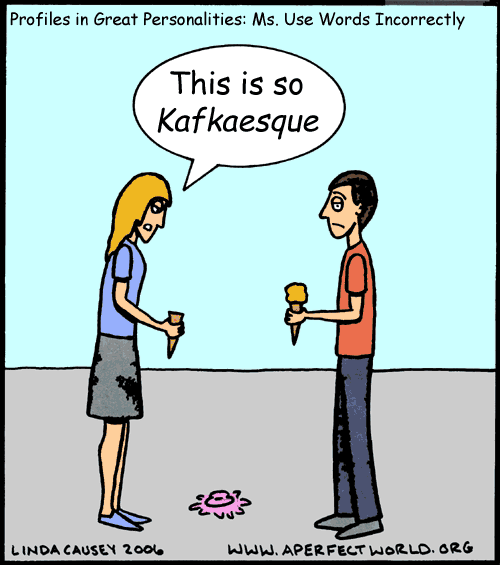

We would be forced to face our own assumption that when people in the developing world, who don't have our same conveniences and cultural norms suffer, that it is less meaningful, less real, less important. This is a difficult truth. It is worth asking hard questions about why these films don't get made--why we as consumers don't want to consume them, really, since I'm sure that the studios would be happy to produce something sure to be lucrative. And while we probably know--or have a good sense for-- the answer to that question (art that is hard on its audience is not generally popular for mass consumption), we should be asking ourselves what can be done to change that--even in small ways.

But in the end, "The Impossible" is telling one story, based on true events suffered by a real family. While it does portray a disaster that disproportionately affected southeast Asians, and not European tourists, we should be outraged at our failure as a society to want to tell--or more importantly, to want to see--such stories rather than at how "The Impossible" cannot tell every story, or convey every political and social message that we believe should be out there. We should look closely at how we view tragedy, and if and why we may feel greater shock and sadness when people who look more like us--whether because they are white, middle-class, from the developed world, English-speaking, etc.--are harmed or killed or suffer than when people who are different endure the same. But it seems unfair to penalize one film, written and produced to tell one specific story, for failing to address all these collective wrongs.